By - Bruce McCall

“Poland’s Sub Goes Glub”

Poland

succumbed just a tad later than most nations to the epidemic of submarine fever

that engulfed the navies of the world around the turn of the 20th

century. Twenty-three years later, to be precise, a large explained by Polish

Naval Chief of Staff Pzdyndzk as the consequence of forgetting to renew the

defense ministry’s subscription to Jane’s Fighting Ships in 1901 and prodli plap

dzynubi,(“just plain missing out”) on world naval developments ever since. But

then Poland awoke; a subscription to Jane’s was fired off. Within months,

submarine fever gripped the Polish naval soul.

Now all

Poland needed was a submarine. The used-sub market proved a bust; those

submarines not lost in a devastating World War had since been broken up under

terms of one or another disarmament pacts. By 1924, a good used one-owner

U-boat was not to be found. Poland must build her own, just as Poland built her

own steam-powered aircraft in 1917.

A

vigorous research and test program followed; the 16 citizens who had them

volunteered their bathtubs and hundreds of individuals participated in

exhaustive underwater trials. Who can forget citizen Jerzy Sdudz of Zakopane,

who set an underwater record of better than 23 hours, and whose widow still

treasures the medal brave Jerzy posthumously earned? And what of the student

body at Krakow’s Polytechnical Institute who performed the painstaking task of

scaling up a four-inch kazoo to 88 feet of gleaming, full-sized sub?

At last, the big day came the dockside scene, a glitter of pomp and circumstance,

Polish style. One token crash dive, then Poland’s pride and joy would surface and

head out for sea trials. Or … would it? The dive was flawless, but eight hours

later the band still stood poised. Dignitaries squirmed and doubts dawned, but

the Prime Minister’s eulogy one week later was upbeat.

“Popli,

Polski!” it began … “Good try, Poland!”

And went

on to stress the importance of all Poles banding together to design and build a

truly modern lug wrench.

“Plucky Ecuador’s Daring Bluff”

It all

began when Colombia violated the 1908 Jute Treaty with neighboring Ecuador by

dumping her jute production on world markets at rock-bottom prices. Six months

later, in the spring of 1941, Ecuador’s jute industry faced ruin, and out of the

bedlam on the floor of Quito’s Jute Exchange rose a cry for justice. Colombia

must pay reparations! But Colombia, under the iron heel of Generalissimo Lopez “Iron

Heels” Lopez y Lopez, was in no mood for conciliation. Quite the opposite.

Claiming “intolerable insults,” Lopez demanded free passes on Ecuador’s new

railway for all his military officers.

Rather

than comply, the proud Ecuadorians blew up the railroad. There was no invasion

as Ecuadorian roads could kill a man. Tensions mounted, then Ecuador acted.

Colombia’s coastline would be blockaded; the naval embargo would throttle her

into a more reasonable state of mind. An Ecuadorian blockade? Generalissimo

Lopez scoffed. What would Ecuador do for a navy? It is not recorded what Iron Heels

said a few days later when aides puffed into the presidential mansion in Bogota

with stunning news. Hundreds of Ecuadorian ships were sitting offshore in a

line that stretched farther than the eye could see! His words, happily, are

lost to posterity, but it is known that Lopez quickly ordered Colombia’s fleet,

the pocket battleship Conchita, a converted banana boat, home from a two-year

goodwill visit to Havana, with orders to run the blockade. A gesture was better

than nothing to the honor-conscious Latins; indeed, it was everything. But even

the gesture came to naught. One sight of that forbidding string of Ecuadorian

sea power fronting the coast of his homeland and the Conchita’s Captain paled.

A few token barrages from a good safe distance and Colombia’s sole sea-born sentinel

streamed away on a goodwill visit to New Orleans. Months dragged by, increasing

Colombia’s hardship and her strangled economy. Army colonels mumbled junta.

Tons of unshipped and unsold jute lay rotting, or whatever jute does, on the

docks. Ecuador’s own just industry revived, then flourished and nine months

after it began, the blockade ended. There it has remained, a sacred symbol of

the chutzpah of a doughty nation. And to this day in Colombia, anybody caught

building or displaying a cardboard cutout of a ship is shot on sight!

“SWASHBUCKLERS

OF THE SEA, BUCKLED IN ONE SWASH”

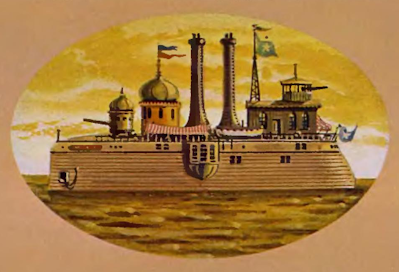

Gleaming

cannon mingling with fluttery awnings, the fighting summer yacht Tanya Chebovka

Smirbovka plied the limpid waters of Lake Gnip in the restless summer of 1909

on a double mission of pleasure and vigilance. Pleasure because Lake Gnip was the

summer playground of Czar Nicholas’ court; vigilance because not even a yacht

was safe in these parlous times from attack by the anarchist Bubkin Clique.

Hence an armed pleasure craft. But it was no use. Engineering dropout Bubkin

merely waited for the Tanya and her cargo of aristocrats to reach the middle of

Lake Gnip—then drained the lake, liquidated his trapped victims, and made the

beached yacht his headquarters. But no use again; days later, czarist police

reflooded Lake Gnip and surrounded the refloated Tanya with armed punts. The

hapless Bubkin and his henchmen were nabbed high and wet.

The USS

Mrs. Millard Fillmore carried a crew of nine and one giant Mode-O-Tone table

radio, left over from an exhibit in the Hall of Sparks at the fabulous 1933 Chicago

World's Fair. Entertainment was her mission; the fleet was in and “Mrs. F.” was

on, serenading American gobs. The Pugh Custard Harmonica Hour or Church of the

Air —no sailor could escape the ubiquitous Mrs. F. and her high-decibel

jollity, blaring across the water for more than a mule. From Pearl Harbor to

Panama resounded that unmistakable din. Not even gunnery practice brought

relief. The merry-making marauder of the U.S. Navy was unstoppable—until one

fateful August night in 1936. Nobody knew which ship sneaked up in the dark and

rammed Mrs. F., tying up her tubes forever; but the immediate scramble

within the fleet to claim blame was, to say the least, unseemly.

Water-borne

man has dreamed of the unsinkable ship since the day he first capsized. And

ever since Nazism first sur- faced, Hitler’s minions plotted to put the idea

afloat for the perverted purpose of war. Thus was born one of the Third Reich’s

most diabolical secret weapons: the heavy cruiser Graf Himmelfarber, with her

ingenious reversible hull. Ach, let the British swine tear her to bits below

the water line; the Graf would simply roll over and start on another hull while

a team of experts patched the damaged one. Let the English scum riddle her

again; over she would roll once more. She had just been launched when a workman

fishing off the bow caught a carp; little did he realize that his “catch” was,

in fact, one more Nazi trick, a bait-seeking torpedo dis- guised as a fish. Up

with a roar went the Graf Himmelfarber. Down in flames came another of Hitler's

evil dreams.

It was

more than just seagoing lingo when tars aboard H. M.S. Contagious were summoned

up to the bridge. Much of this cast-iron leviathan of the sea lanes was a

bridge over England’s scenic River Wumble until 1923 when dire flaws in the

navy's new Fitz & Blithery Sea Mouse carrier biplane fighter called for

drastic cures. The defense ministry saw the bridge as just what it so

desperately needed; its arched structure was the key. By giving the plane a

rolling downhill start, that steep forward deck did what a 91-hp engine

couldn't ... got it airborne. Success? No, disaster, for aviation’s unbending rule

says that what takes off must sooner or later land. Sea Mice by the droves took

off without a hitch. Sea Mice by the droves landed, rolling uphill on that

steep aft deck, hesitated, stopped . . . then rolled right back down again like

stones into the sea, kerplunk! Bad show, gentlemen.

“Albania

Girds for Four-Way War”

What did

it matter that uny Albania was not really men- aced from all four sides, so

long as tiny Albania thought she was? Enemies were everywhere the keyed-up

Albanians looked in 1927, and they looked everywhere: to the north and

Yugoslavia; to the east and more Yugoslavs, not to mention Romanians and

Bulgarians; to the south and Greece; and west lay Italy. Some called it Balkan

paranoia, but the Albanian naval chief of staff, Admiral Luhixu, called it an

emergency. The country went on round-the-clock alert, or as much of an alert as

Albanians could summon. The air force flew himself into exhaustion on patrol.

And the unique destroyer Abnax Nerpi was christened—four times, once for each

of her quartet of prows. What a master stroke for a nation whose pinched purse

allowed only one man-o'-war yet who had to defend herself in several directions

at once! Here was a ship to blast the Yugoslavs closing in from the north while

broadsiding the Romanians and Bulgarians on the east and spitting fire at the

Greeks attacking from the south and still dealing salvos to the Italians in the

west. The Abnax Nerpi was indomitable, impregnable—and, alas, un- navigable. In

fact, berserk. The over-bowed destroyer took a shakedown cruise and shook

herself to smithereens, going down with Admiral Luhixu standing—fittingly,

somehow— at what he deemed to be the helm. Fair Albania, bereft of what seemed

a brilliant means of defense, was left waiting for the imminent invasions to

begin; at last report she still was.

“Holy

Imhotep it’s Moving”

The

desert heat plays strange tricks on a man’s eyes, but this was ridiculous—a

distant pyramid off on the Suez skyline, not just floating in the fierce

noonday sun but seeming to move steadily south at a good four knots! Surely, 1t

was a mirage brought on by the heat, the lack of water or an extra helping of

couscous. But no, it was a pyramid moving steadily south at a good four knots.

And not just any old pyramid but the most lethal pyramid ever conceived,

something to boggle the wiliest mind of the highest high priest in Imhotep’s

temple. It was Imhotep, Jr., the desperate last-ditch gambit of Cairo’s clandestine-warfare

plotters. This sly masterpiece of Arab subterfuge may have looked to casual

eyes like just another harmless old stone pile—but underneath that au- authentic

facade bristled a gunboat load of shot and shell. Come darkness and the

Imhotep, lurking in some unexpected spot, would open up on nearby Israeli positions,

raining down a hail of Arab ammo. Come dawn and a bruised and baffled enemy

would find no gun emplacements to snuff out. Only an empty desert with its

ever-constant pyramids. The brilliant ruse worked. Deadly Imhotep's guns

flashed nightly and Cairo rejoiced. Alas, the eager Arabs could not leave well

enough alone; a fleet of 22 more death-dealing decoys soon studded the Suez.

One pyramid, yes; two, maybe—but a traffic jam of pyramids? Something was

definitely not kosher. Israeli guns boomed, Cairo’s crafty pyramid club came

tumbling down and another Arab jig was up.

“The Day the

Banzai Died”

Japanese

spies fanned out across the Pacific as the 1930s dawned and the Rising Sun

rose. Their orders were clear; Bring home plans of the latest foreign warships;

lie, steal, kill even buy anything to help build a modern fighting fleet. The

battleship Goto Jairu was one triumph of this sinister espionage assault but a

coup that all too quickly curdled into tragedy.

Launched

in November of 1936 after a crash construction program and a blaze of

publicity, the 1,500,000-ton silver monster puzzled naval savants. She looked

to the expert eyeless like an up-to-date battlewagon than some mighty, hellish

toy. Was that giant hull really cast in lead, as it seemed? Why no guns? What

to make of a battleship with a superstructure of two huge funnels, period? And

could a flat-bottomed battleship even float? The Goto Jairu drew awed gasps as

she slowly, majestically backed down the slips; but the roar of a million banzais

faded and died when she slithered in one long breath-taking slide straight to

the bottom of Tokyo Bay. What had gone wrong? Nippon’s lips were sealed, but

captured Jap documents squealed; postwar sleuths pieced together a bizarre tale

of espionage run amuck. Present in an honored place at the ill-fated launching

had been the junior Japanese spy known to Westerners only by his code name, Mr.

Nice Boy, a rather dim lad who took up espionage only after failing in an

earlier career as an abalone slicer. Mr. Nice Boy had sailed to America in 1932

but misread instructions. Instead of working in a ship in Washington, as

ordered, the hapless Jap ended up toiling as an obscure shipping clerk in a

Waltham, Massachusetts, novelty-and-game factory. After two years, he suddenly

returned to Japan, where his suicide by hara-kiri scant hours after the Goto

Jairu fiasco, though little noted at the time, proved the key to everything.

Sending a clue in the movements of the shadowy Mr. Nice Boy, investigators

retraced his steps in America. And there it was, in a yellowed clipping from

the back pages of the Waltham Daily Hue & Cry; the answer to both the

riddle of the Goto Jairu and Mr. Nice Boy’s messy end. “Strange Incident at

Local Factory,” ran the minor squib. “Officials Baffled by Theft of Mold for

Toy Battleship used as Marker in Popular Monopoly Game.” The eager Mr. Nice Boy

had done his job not wisely but too well – and Japan’s plan for naval supremacy

and world conquest never passed Go!

No comments:

Post a Comment